0

In

May 1895, the first official cat show in New York City took place at

Madison Square Garden. More than 200 felines ranging from humble street

cats (such as Brian Hughes’ Nicodemus) to the high-society cats of Mrs. J.J. Astor and Mrs. Stanford White were all on display at the first National Cat Show.

In

May 1895, the first official cat show in New York City took place at

Madison Square Garden. More than 200 felines ranging from humble street

cats (such as Brian Hughes’ Nicodemus) to the high-society cats of Mrs. J.J. Astor and Mrs. Stanford White were all on display at the first National Cat Show.Although they did not take home any ribbons, a trio of black cats belonging to Colonel William D’Alton Mann, publisher of the Town Topics society magazine, were the center of attraction that year.

According to Helen Maria Winslow, author of “From Concerning Cats: My Own and Some Others,” the three cats were named Taffy, The Laird, and Little Billee. They were all jet black and 14 months old. The New York Times reported that the handsome cats reposed on a red cushion and slept for most of the time.

Although The New York Times article claimed the cats were named Little Billie, Leo, and David, I’m more prone to believe that Ms. Winslow has it right. (I also don’t think Leo and David are suitable names for cat-show participants.)

Not only was Ms. Winslow familiar with Colonel Mann and his office cats, but Taffy, Little Billee, and The Laird were popular names during this time: These were the names of the leading male characters in a long-running play called Trilby, which was based on the 1894 novel by George due Marurier. Trilby had opened at the Garden Theatre on Madison Avenue just one month before the cat show.

When this

photo was taken in 1895, Trilby was on the Garden Theatre marquee. The

theater, on the southeast corner of Madison Avenue and 27th Street,

opened on September 27, 1890, and closed in 1925. New York Public

Library Digital Collections

According to Ms. Winslow, Colonel Mann was a devoted lover of animals who had a standing order: Should any of his employees see a starving kitten on the street, they were not to leave it to suffer and die. Hence, the Town Topics office was a sanctuary for unfortunate cats. As Ms. Winslow writes, “One may always see a number of happy-looking creatures there, who seem to appreciate the kindness which surrounds them.”

Had Colonel Mann only exhibited some of that same kindness toward his readers, he may have avoided numerous lawsuits and prison time.

Colonel Mann, the War Hero and Extortionist

Colonel William D’Alton Mann during the Civil War.

Born in Sandusky, Ohio, in 1839, Mann grew up on his father’s farm and was one of thirteen children. From this simple start, he epitomized the American dream.

Mann was a Civil War hero at Gettysburg, an entrepreneur and inventor (he invented a luxury railroad car called the “Mann Boudoir Car”), and later a business tycoon, millionaire, and publisher. He was also a family man who doted on his daughter, Emma, and his office cats.

Alas, Colonel Mann also was a dirty blackmailer who extorted tens of thousands of dollars from New York’s millionaires via a column called “Saunterings” in Town Topics.

The Town Topics Bribery Scam

The weekly magazine had been founded in 1879 as J.R. Andrew’s American Queen, a National Society Journal. Louis Keller (founder of the Social Register) took over in 1883, and under his editorship, the publication was “dedicated to art, music, literature, and society.”

When the publication went bankrupt in 1885, William’s brother Eugene purchased it and renamed it Town Topics. Under Eugene D. Mann’s reign, the weekly magazine morphed into a scandal sheet that often identified high-society wrongdoers by name.

Colonel

Mann (left) with Colonel Clem the Gettysburg Reunion of July 1913,

which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Much to the dismay of the Vanderbilts, Goulds, Morgans, and other millionaires, Mann took the art of scandal to a mastery level that would have put publications like today’s National Enquirer to shame.

Town

Topics was part high-society rag / part elegant weekly that published

promising literature, sporting news, and financial advice.

Many articles have been written about this Town Topics scandal, so I’ll sum it up in a few sentences.

What Colonel Mann did was establish a network of paid spies comprising servants, telegraph operators, hotel employees, seamstresses, butlers, and grocers to spy on the socialites and supply the magazine with juicy gossip.

Mann would then meet with the “guilty parties” at his favorite place–Delmonico’s–where they could negotiate for discretion.

The amount of money that Mann managed to extort from America’s wealthiest men was staggering. For example, William K. Vanderbilt paid $25,000 (that’s over $700,000 today), Charles M. Schwab paid $10,000, and Senator Russell Alger paid Mann $100,000 in shares of his lumber company’s stock.

This

illustration appeared in the January 25, 1906, issue of The Inter

Ocean. The article’s headline was: Some of the Fruitful Shrubs Colonel

Mann Has Watered in His Town Topics Garden in New York.

Colonel

Mann expanded his scandalous publishing empire in 1900 when he founded

Ess Ess Publishing Company to produce The Smart Set.

Despite all this paranoia — or maybe because of it — Town Topics was the most widely-read magazine in society (of course no one would ever admit to subscribing to it).

Taffy and the Town Topics Cats

The Town Topics office cats made their home at 208 Fifth Avenue (aka 1128-30 Broadway), a Renaissance Revival designed by Berg & Clark for Alfred B. Darling in 1894. (Prior to this date, the address was a five-story brick and brownstone building occupied by the Chesterfield Hotel in the 1870s. See photo below.)

The new seven-story building at 208 Fifth Avenue had frontages on Broadway and Fifth Avenue and housed stores and offices. Until the Cross Building was constructed at 210 Fifth Avenue around 1904, a narrow, vacant lot separated the building from the famous Delmonico’s restaurant, which was on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 26th Street from 1876 to 1899.

This

photo of Delmonico’s was published in the King’s Handbook of New York

City in 1892 — two years before the brick and brownstone buildings to

its left were demolished to make way for the new office building at 208

Fifth Avenue, where the Town Topics cats would make their home.

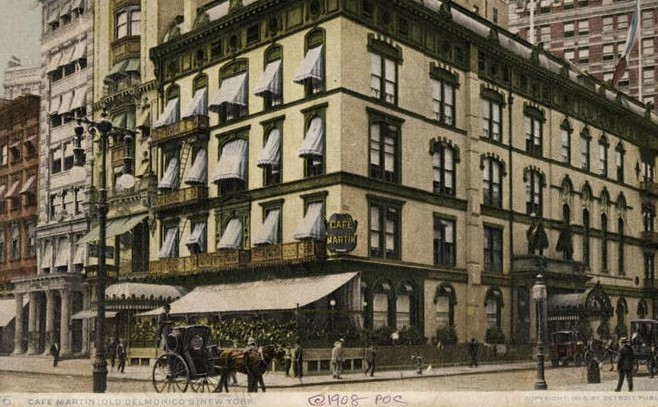

In 1902 when this photo was taken, the Cafe Martin was

leasing the building that had been home to Delmonico’s restaurant from

1876 to 1899. The Town Topics office at 208 Fifth Avenue is to the left

and the St. James Hotel is in the background. Museum of the City of New

York Collections

Following this tragedy, Colonel Mann put up a strong wire grating across the windows. From that point on, Taffy, described as a “monstrous, shiny black fellow,” was the leader of the Town Topics cat colony.

In

this closeup of the top floors of 208 Fifth Avenue, you can see the

marquee for Town Topics and the windows from which The Laird and Little

Billee made their fatal leaps to the pavement below in the late 1890s.

The bribery continued to escalate, leading to numerous lawsuits, and, in 1905, to the arrest of Colonel Mann on charges of perjury (the complainant in this case was Robert J. Collier of Collier’s Weekly). Mann’s daughter, then Emma Mann Wray, bailed him out by offering as collateral the vacant lots at

810-828 West 38th Street, where Mann was building new offices for Ess Ess Publishing (now a parking lot across from the Jacob Javits Center).

Mann was ultimately cleared of perjury, but by that time Town Topics lost most of its bite. Two years after Mann’s death in 1920, A. Ralph Keller organized the T.T. Publishing Company to buy Town Topics. The paper lingered on until eventually folding in the 1930s.

Here’s

another photograph of the Cafe Martin in 1908 — but this time it has a

new neighbor to the left: The skinny Cross Building at 210 Fifth Avenue.

The Lincoln Trust Building where Town Topics once presided is to the

left.

Here’s another view of 206 – 212 Fifth Avenue taken from the vantage point of Madison Square Park. NYPL Digital Collections

A colorized photo of from 1908.

A colorized photo of from 1908.

By

1915, when this photo was taken, Cafe Martin, which closed in 1913, had

been replaced by a towering office building. Museum of the City of New

York Collections

In

1919, four years after the Franklin Trust moved out, the ground floor

of 208 Fifth Avenue was home to Charles W. Ackerman’s hat store. Charles

was known as “The Hat Specialist.”

Today,

all the buildings look pretty much as they did 100 years ago. The old

Town Topics office is now one of 12 cooperative loft units that sell for

about $2.5 million. Pet cats (and dogs) are permitted. Photo by P.

Gavan