http://arstechnica.com/science/2016/08/meet-the-worst-ants-in-the-world/?utm_source=pocket&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=pockethits

Meet the worst ants in the world

Argentine ants have invaded every continent in just one century. Can they be stopped?

Tom Campbell

I battled the ants for about a year before I started noticing interesting patterns in their behavior.

My military tactics against the invaders were those of a typical San Francisco eco-nerd. I used non-toxic spray made with orange peels to repel them (it actually works pretty well) and placed low-toxin poison sugar bait traps close to cracks they used to enter the house. But these tiny, brown insects seemed unstoppable. They would swarm onto their targets seemingly out of nowhere. I’d put out my cats’ food and come back in 45 minutes to find a thick, wriggling line of ants moving between a crack in the wall and their kibble target. If I blocked their trail with poison, they'd pour out of a different crack next to the kitchen counter. Or at the base of the stairs. Or in my bathroom.

By necessity, I spent a lot of time watching these tireless insects overcoming every obstacle. And during all that reconnaissance, I started to see things that made me wonder who these ants really were.

As my neighbors watered the plants in our backyard, I watched ants boiling out of cracks in the brick patio, racing to escape the onrushing tides. Looking more closely, I discovered they were carrying tiny white bundles in their mandibles. I recognized eggs and larvae. The ants were rescuing their brood from a flood apocalypse caused by oblivious humans.

Later, when surveilling a trail of ants marching across my kitchen counter, I spotted one that was enormous—twice as big as a typical worker, with an elongated, bullet-shaped abdomen. I was watching a queen ant marching through my kitchen. The experience gave me chills; there was something genuinely awe-inspiring about seeing a queen in person. I had never heard of ant queens wandering around in the open. I guess I thought they were egg-laying machines, like the Queen in Aliens, and never left the deepest confines of the ant nest.

I snapped a picture and started comparing it with online images of California queen ants. Quickly, I figured out this queen was a member of Linepithema humile, known colloquially as Argentine ants (though they also come from Brazil and elsewhere in South America). Now I understood the magnitude of my problem.

One of the world's most invasive ant species had taken up residence in my house.

The world of Linepithema humile

L. humile isn't your stereotypical ant, with one queen and many workers laboring in a single nest. Argentine ants have multiple queens per colony, and there can be as many as 300 queens for every 1,000 workers. This makes them virtually impossible to kill with poison bait traps, which work on the principle that workers bring the tasty toxins back to the queen, whose death destroys the colony. When you have a lot of queens, that's not an effective strategy.

Argentine ants are unusual in another way, too. They don’t build one large nest with lots of tunnels and rooms. Instead, they live in constantly shifting networks of temporary, shallow nests that change from day to day. Their ability to move quickly in large groups is what helped them swarm on my cats’ food so fast—and it’s why they were able to pack up their eggs and flee the flood in my backyard like well-trained disaster workers. Even when they aren’t running away from human gardeners, they move their eggs between nests all the time. Queens and workers are used to transiting from nest to nest, rarely staying put for long.

Despite their name, Argentine ants have now lived in the United States for more than 120 ant generations, which are roughly a year long due to their short lifespans. It’s been a struggle. The environment in North America is dramatically different from the tropical ecosystems where the ants originally evolved. These ants had to become an urban species to survive, living almost exclusively in cities and agricultural areas where plumbing and irrigation provide the water they desperately need. Entirely thanks to humans, Argentine ants have now become the dominant ant species in California cities, driving out dozens of native species. Today they've actually invaded most major landmasses in the world, including North America, Europe, Australia, Africa, Asia, and quite a few islands.

The Argentine ant's progress across the globe echoes humanity's own. Staring at my uninvited house guests had inadvertently drawn me into one of the most fascinating stories of species invasion in recent history.

JUMP TO ENDPAGE 1 OF 4

Insect immigration in the 19th century

For nearly two centuries, the fate of L. humile has been deeply entwined with the fate of H. sapiens. It started when the ants arrived in California—they arrived just like humans would, by riding on cargo ships.

In the jungles of South America, L. humile lived in relatively small colonies centered around trees. Though they can eat virtually anything, Argentine ants like to cultivate aphids and scale insects, milking these leaf-eaters for their sugary "honeydew" excretions. We don't know a great deal about the ants’ predators, but entomologists like Alex Wild have observed wars between colonies in their native ranges. It's possible that these intraspecies hostilities kept their populations in check.

Wild also notes that there's really "nothing special" about this ant that has colonized most of the world in just a century. "The workers are cheap and featureless," he said. "They don’t have thick armor or extensive spines [like other species]. They are pretty flimsy." Every evolutionary development is a tradeoff, and the Argentine ants survive by making what Wild called "a cheap robot army." In their home ranges, these flimsy ants live at a pretty low population size, no doubt menaced by their more impressively armored neighbors.

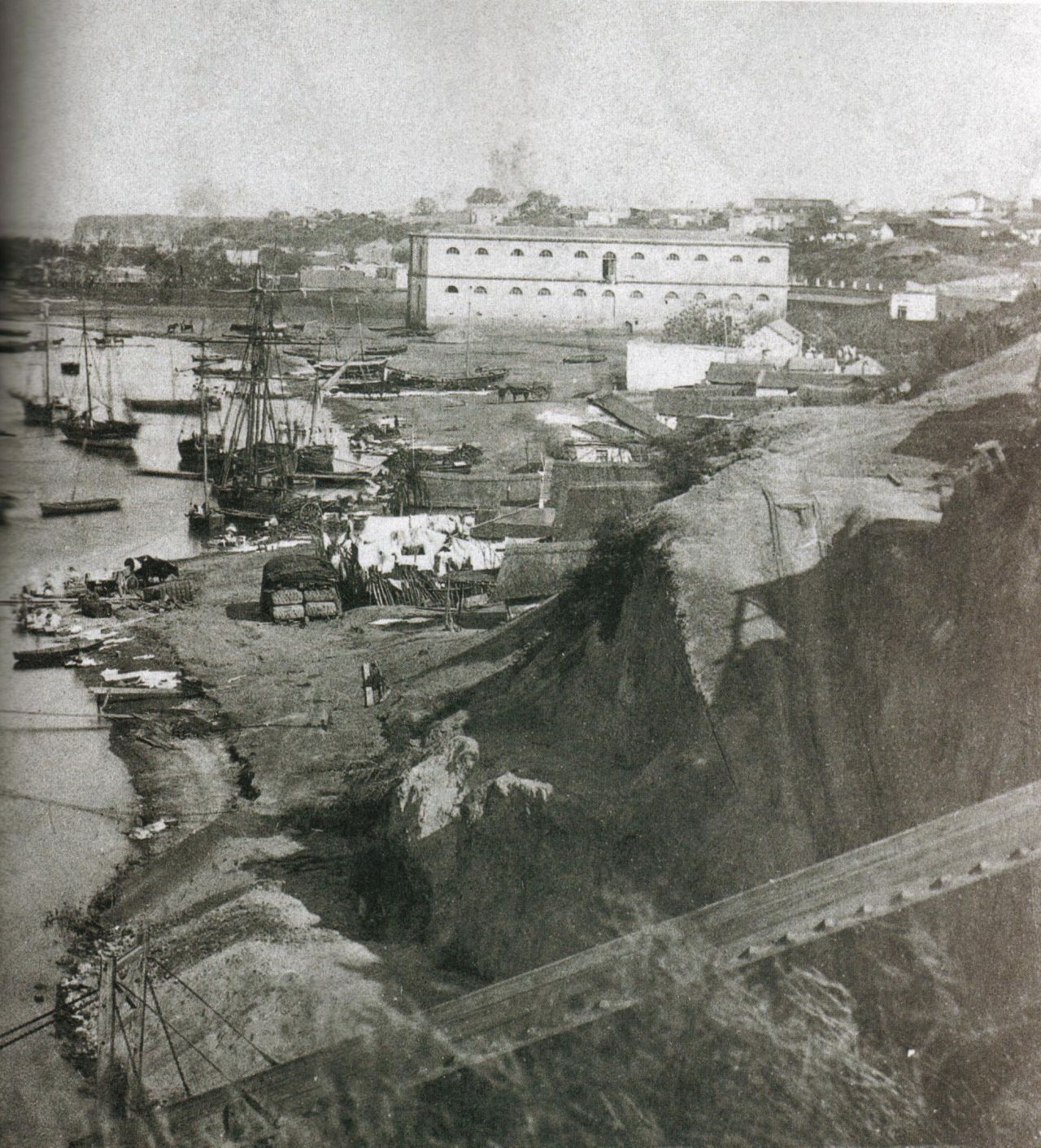

Enlarge / Puerto Rosario in 1868, when Argentine ants probably started getting on board and finding their way into the world. Genetic analysis reveals that most Argentine ants in the world can trace their lineage back to ants living near this port.

But in the 19th century, things began to change. Humans disturbed the ants’ habitats, converting kilometers of trees into cities that serviced international companies devoted to the import and export of everything from sugar to slaves. It’s impossible to say when the first Argentine ants in a port city trundled aboard a cargo ship, headed across the Atlantic among the other plants and animals. Entomologists' first recorded sightings of the ants outside South America are in New Orleans and the island of Madeira, off the coast of Portugal, in the 1880s. Tellingly, both were ports used by ships coming from Argentina.

A map of the shipping and train routes the Argentine ants took to get to California from Port Rosario. Red dotted lines are cargo shipping routes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and blue shows the Sunset Limited track, a train that ran between the port of New Orleans and Los Angeles in the early twentieth century. Map created with Mapzen Tangram.

UC Berkeley environmental scientist Neil Tsutsui helmed an effort to sequence the genome of L. humile, in part to find out where the invading group had originated. He and an international team of colleagues published the results of their analysis in 2011. They compared the genomes of Argentine ants in California to those of native populations, and Tsutsui told Ars that they were initially surprised by the results. “I was expecting Buenos Aires to be the source, but it was actually a city upstream called Rosario,” he said. “It turns out that in the late 19th century, when the ants were moving around, Rosario was actually a bigger shipping port than Buenos Aires. So it made more sense as a source for introduced populations.”

Genetic evidence supports the idea that the ants made their way from Port Rosario all across the globe. Subsequent sightings of the ants in the United States show that they also hitched rides on trains from New Orleans, ultimately arriving in California in 1904. Trucks probably transported them throughout the state. But how could such fragile creatures survive these journeys in giant machines and go on to found insectile empires? With their countless queens and nomadic lifestyle, they turned out to be the ultimate adapters.

The seasons of an ant's life

In biologist Deborah Gordon's lab at Stanford, there is a small group of researchers who observe Argentine ants in the wild. Which is to say, they go to a small, triangular copse of trees on campus bordered on all three sides by asphalt walkways. Because Argentine ants are adapted to human landscapes, the best places to find them are, well, among humans. On a cloudless afternoon in late July, I joined undergraduate researcher Dylan MacArthur-Waltz on his rounds to check on the local nests.

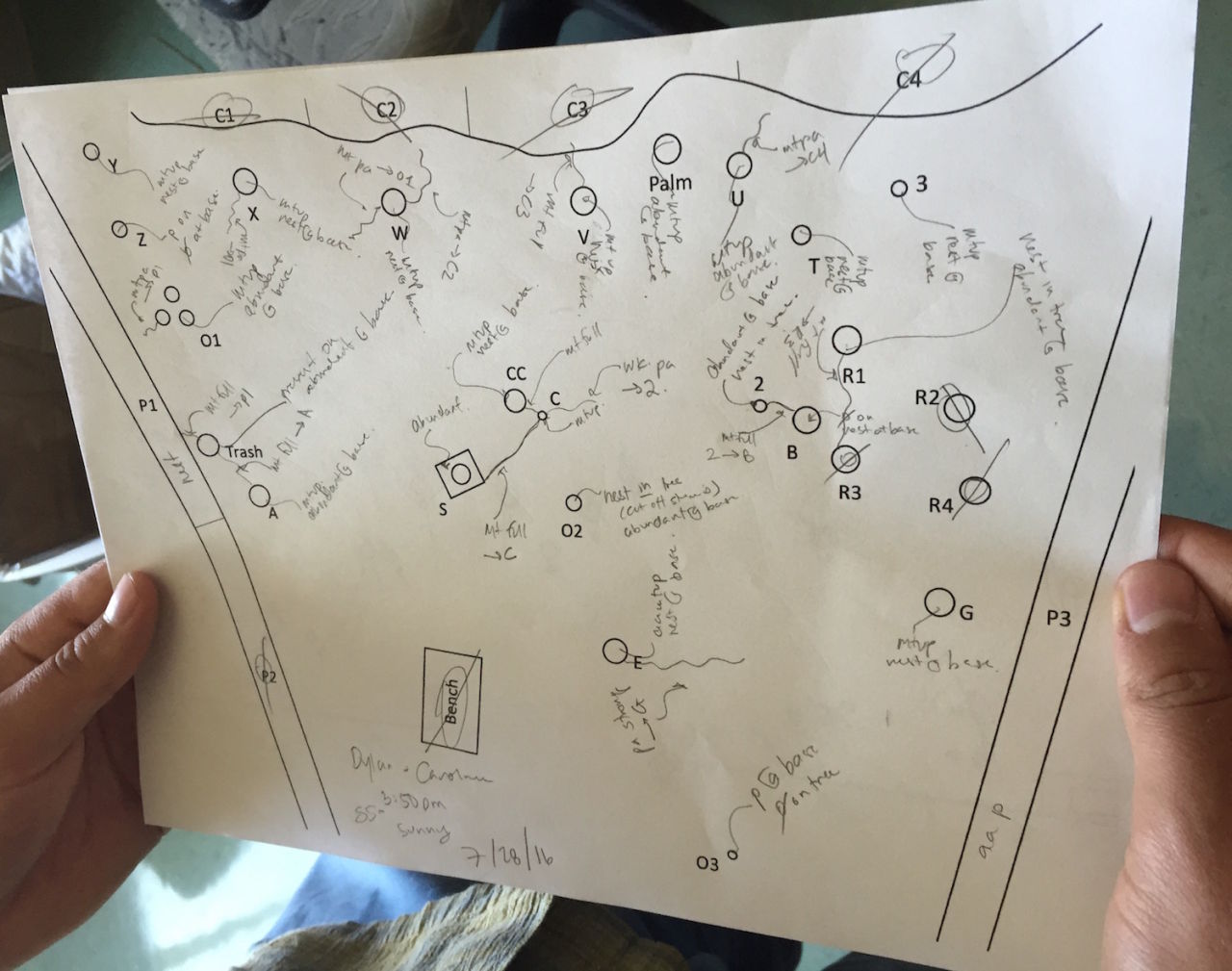

To track the insects' ever-shifting nests, researchers like MacArthur-Waltz draw ant maps. Trees (and one trash can) are represented as large circles and serve to orient us in the survey area. We look for cracks or holes where ants are crawling in and out; those are labeled carefully on the map as nests. Trails are squiggly lines drawn in pencil. Some trails lead to other nests, but others lead up into the treetops where the ants cultivate their aphids. Ants clambering back down the tree trunks have been feeding on honeydew; their abdomens are distended and translucent. "That's how we can tell they're eating something up there," MacArthur-Waltz explained, pointing at the swollen ants.

Enlarge / Dylan MacArthur-Waltz holds an Argentine ant map, part of his research in Deborah Gordon's lab at Stanford University.

Annalee Newitz

If there's any pattern to the Argentine ant network at Stanford, it's "chaos and adaptability," he said. Deborah Gordon, who heads the lab where MacArthur-Waltz is doing his research, said Argentine ants generally have 20 to 30 nests as part of their ever-evolving network. Individual ants follow trails between the nests, and there are queens and brood spread across several nests in the network. As we crunched through leaves in search of trails, MacArthur-Waltz explained that he has been checking on the ants since last year, witnessing one cycle of L. humile's seasonal transformation.

During winter, the network of nests shrank down to just two, both situated in sturdy trees. The rest of the area was taken over by another species called Winter Ants. As spring approached, the Winter Ants retreated and the two Argentine ant nests expanded into their complex network of 20 to 30 nests within weeks. Within this microcosm, it becomes easy to see how these ants might expand to take over every continent in the world.

Enlarge / Argentine ants tending scale insects, similar to aphids, on an orange tree in Davis, California. The ants milk the insects for sugary "honeydew" excretions.

But spring isn't just about expansion. For Argentine ants, it's also time for their annual sacrifice. Hidden from human eyes, in shallow tunnels beneath tree trunks and underground, the worker ants kill 90 percent of their queens. By one estimate, the queens go from 30 percent of the population to less than five percent. It's hard to say why the workers would do this at the beginning of their mating season; Tsutsui called it "mysterious and bizarre behavior." So far, scientists have not been able to figure out whether this annual sacrifice changes the genetic makeup of the colony. It seems that the queens are killed with little regard for age, fitness, or genetic relatedness to the rest of their sisters.

After the queens have been executed, mating season begins. MacArthur-Waltz showed me a line of ants bearing a tiny white brood from a nest entrance at the base of their winter nest tree, along a low, shady branch, and into another nest through a crackled knot in the bark. The results of mating season are everywhere, though there are still some queens and males waiting to hook up. At home in my San Francisco backyard, I watched two winged males walking unsteadily along a trail between nests. For a brief period every year, unmated queens and males grow wings so that they can fly to new nests, bearing genetic diversity with them. The males I saw were probably about to fly away, or they had just landed and were prowling for some local queen action.

JUMP TO ENDPAGE 2 OF 4

Urban invaders

When I asked Gordon about the ants in my house, she explained that they've probably been living in a nest they've built in my house. I can see the ants on busy trails between their nests in my backyard and fractures in the exterior of my house. Now I imagine them in the walls, winding around old crusts of insulation and century-old support beams.

L. humile rely on built structures for shelter and water. "In San Francisco, we have two peak periods when they come inside," Gordon explained. "In winter, when it rains, they come in on the pipes because it's warm and dry inside. But the peak time is in September and October when it's hot and dry outside. They find their way inside by tracking humidity condensing off the pipes. If they come into [your house] and find someplace that's hospitable, a queen and some workers will move in." Contrary to popular assumptions, the ants aren't coming inside to get your food. Mostly they want water, and "food seems to be only an extra bonus," Gordon said.

So if you're wondering why your house is invaded like clockwork every winter and summer, the answer is this is actually part of Argentine ants' natural lifecycle. They live in the exact same habitat that you do. From the ants' perspective, you're trying to displace them from a house that is rightfully theirs—and they would drive you out if they could. That's the same strategy they've used with most of the native ants in San Francisco.

To protect territory, Argentine ants will attack other ants, but mostly they starve out other species by consuming resources. Wild summed up their strategy by comparing them to Walmart:

Their colonies are connected over a vast scale, so individual nests can operate for a long time at a loss until they drive competitors out of business. In California, the native ant colonies are local and smaller. Argentine ants are in these sprawling colonies that can import resources from somewhere else. They can operate satellite nests at a loss like these big franchises.

Argentine ants wreck natural ecosystems by pushing out the local ants. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign entomologist Andy Suarez told Ars that native ants provide valuable services to the environment, and when Argentine ants push them out, the effects are felt across several species.

For example, California harvester ants bury seeds deep in the ground and aerate the soil, which is good for trees. But when Argentine ants drive out harvester ants, the soil is less absorbent and trees don't get as much water. Additionally, coastal horned lizards have a lot of harvester ants in their diets. Without harvester ants, these lizards may die back or worse. "Displacement of native species results in cascades in the ecosystem," Suarez explained. Ultimately Argentine ants aren't just killing other ants—they're harming trees and lizards, too. The loss of those trees and lizards will affect other species, and so on, until you're looking at potentially dozens of extinctions caused by one very persistent group of pests.

From war to supercolonies

Suarez, who has mapped the ants' global expansion, said they've colonized the US at an astonishing rate because they reach new habitats at unnatural speeds. Like humans, they move around in trains and trucks. That's the only way to explain why the first recorded sighting of Argentine ants in California is in 1904, less than two decades after they were first seen at the port of New Orleans—there is simply no way they could have walked that distance so quickly. Tellingly, most early sightings of Argentine ants in the US are in cities along the Sunset Limited train line, which traveled from New Orleans to Los Angeles via Texas.

So thanks to modern transit, one small group of ants from Port Rosario was able to colonize most of the US and most of the world. This created a genetic bottleneck known as a "founder effect," where the gene pool shrinks each time a single population founds a new colony, that colony founds another colony, and so on. As a result, almost every single Argentine ant in California is closely related. Genetically, they form what some researchers call a "supercolony." The California supercolony is also closely related to supercolonies in Japan and Spain. And this has led to a strange new kind of behavior among these ants.

Enlarge / Argentine ants in Australia eat sugar water together.

As noted earlier, South America's native Argentine ants battle—one colony will fight the ants from other colonies. Gordon explained that each ant has a thin layer of grease covering its entire body, which other ants can smell to figure out where the ant is from and what it has been doing recently. Tsutsui says that any ant that smells like another colony will be attacked. But this almost never happens in California. When Argentine ants from different colonies meet, they sniff each other and move along. Same goes for Argentine ants from Japan and the Mediterranean. Put an international group of ants together in the lab, as one group of researchers did, and they treat each other like peaceful nestmates. Gordon cautions that this doesn't mean that all Argentine ants in California are functioning as one colony; they aren't sharing food, nests, or brood. But they're not making war on each other, either.

The invasive version of the Argentine ant has become genetically and behaviorally distinct from its ancestors in South America. Losing the urge to fight each other has obvious advantages, too. Inter-colony war no doubt kept their populations in check back home. But in California, they can expand without fear of any natural predators, including themselves.

JUMP TO ENDPAGE 3 OF 4

Ant communication

This isn't to say that ants aren't dangers to themselves at times. Case in point: unhappy humans often discover huge piles of dead Argentine ants in their freezers. Why would the ants keep crawling to their icy deaths after so many of their sisters had died? It was a complete mystery until Gordon, Tsutsui, and other researchers unlocked a clue about how these ants communicate. Like most ants, L. humile conveys information to its peers through chemicals called pheromones. They can mix dozens of chemical combinations from organs all over their bodies, releasing them into the air as volatiles or leaving them in tracks on the ground. Possibly the best understood of these communication signals is a simple trail pheromone, a mix of two chemicals that an Argentine ant lays on the ground to tell her sisters "follow this!"

What's unusual about Argentine ants is that they lay trail pheromone constantly. This can help the ants recruit each other for their rapid-fire food foraging operations ("Just follow the trail I already made!"), but it can also be deadly if the trail leads into a freezer. Gordon thinks the icy ant graves were the result of one way the trail pheromone system can go awry. Some enterprising ant found an attractive scent in the freezer lining, climbed into the freezer, then froze to death before it could escape. Her sisters trundled along after her, and the more who came, the more trail pheromone they left behind. Eventually this would result in a weird, ever-growing pile of frosty ants—along with some seriously frustrated humans who don't like to eat food covered in dead insects.

At Tsutsui's lab in Berkeley, researchers are trying to crack the code on ant pheromones. They've gotten far enough that you might say they can communicate in Argentine ant language a bit. To do it, the team used a gas chromatograph and mass spectrometer for chemical analysis, plus low-tech paper and wires for manipulating the ants. First, researchers painstakingly analyzed chemicals left behind by ants who walked across wires to reach food. Their goal was to decode the ants' trail pheromone, which turned out to be a combination of two chemicals that attract other ants. Next, Tsutsui's team synthesized its own version of the chemical to see whether it would attract ants. It did. Adding another ant pheromone to the mix made the trail even more attractive, so Tsutsui believes they've now found two chemicals that act as ant attractants. The team then figured out how to change the chemicals on an Argentine ant's skin so her sisters no longer recognize her as a nestmate. At that point, the ants attack each other. After these experiments, humans essentially know two phrases in Argentine ant pheromone language: "Follow this trail!" and "Attack!"

Enlarge / A feisty little Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) attacks a much larger fire ant (Solenopsis invicta). Both species co-exist naturally in subtropical South America, but in the southern United States where both have been accidentally introduced, the fire ant has displaced the Argentine ants. Austin, Texas, USA.

Though the ants are using possibly hundreds of other chemical combinations to communicate, Tsutsui thinks we know enough now to change the way we deal with the pests in our homes. "If you put out a liquid bait with pheromones, you can attract more ants and use less insecticide," he said. "The goal is to reduce insecticide, using the ants' own language to alter their behaviors." Next, Tsutsui wants to decode the ants' alarm pheromone: "When you have them on a trail and you breathe on them, they'll scatter and freak out. That's because they're emitting an alarm pheromone, an alert that something scary is happening. It's a volatile chemical diffusing through the air. We want to identify what that is." There are obvious uses for alarm pheromones in pest control, too.

Gordon has found that pheromones are just one part of the ant language equation. As she explains in her fascinating book Ant Encounters: Interaction Networks and Colony Behavior, ants do not have a hierarchical structure where the queen tells the workers what to do. Instead they have an emergent intelligence where ants figure out what to do by keeping track of what everybody else is doing. As the ants pass each other on trails or in the nest, they use their antennae to smell the grease on each other's skin. Different activities change its smell—an ant can tell when its sister has been working in the nest, foraging outside, gathering food, or working cleanup duty.

In the Stanford study area, researchers have put a stroke of yellow paint across a popular foraging trail. Researchers count the ants as they pass over the mark and use the data to test the ant counting hypothesis.

The ants keep track of the rate at which they meet other ants doing each job, and if they notice a sudden uptick in ants with food from outside, they are likely to drop what they are doing and start foraging. Same goes for any other duty. The more ants who are doing something, the more likely it is that others will start doing it, too. In this way, Argentine ants divide up labor based on what needs to be done rather than on some pre-ordained plan. This could explain why many ant colonies have a large group of "lazy ants" who just sit around in the nest doing nothing. They are waiting to be activated by a pheromone or a number.

Argentine ants' complicated behavior contradicts what we see in popular movies like Antz, where each ant is assigned a role at birth and does it until she dies. Instead, L. humile behavior is dynamic. A janitor might become a forager if needed. It all depends on what they smell and how many ants they encounter on the job.

Can there ever be peace between humans and Argentine ants?

Nobody I interviewed for this article would say anything nice about Argentine ants. Wild compared them to the Borg, the Star Trekbaddies who exist only to assimilate other species. Gordon said she won't keep them in her lab because they might get into the other ants' containers; she spends more of her time with harvester ants. Suarez started his description of their negative impact on the environment by saying, "I don't want to be a species-ist, but..." Even Tsutsui, who is trying to communicate with the ants, hopes his discoveries will help us make better insecticides. Unlike native ants, Argentine ants provide no services to the environment. They kill their neighbor ants and invade human homes. The best you can say about them is that they are "adaptable," as MacArthur-Waltz noted.

Put another way, Argentine ants are a lot like industrialized humans. To fully rid ourselves of Argentine ants, we would have to shed the lifestyles we've gotten used to as an urban species. That means giving up our lawn sprinklers fed by those water pipes the ants love to use as drinking fountains. We'd have to learn to adapt to the natural ecosystems in the lands that we've invaded, rather than trying to turn every ecosystem into a lush, green paradise. In California, Suarez said, it would be as easy (or as difficult) as allowing our environment to return to its natural, dry state. "Argentine ants really require a much wetter environment than California naturally provides. Cities create the water." All we need to do is get rid of our "green lawns," planting "chaparral and sage [to promote] environments that are great for natural species and that would dry things out enough that Argentine ants wouldn’t show up." Wild agreed with Suarez: "Just stop watering your lawn and you'll solve the Argentine ant problem."

My neighbors and I have already tried this; our backyard is planted with native succulents and flowers. And yet as I raked last week, I discovered two new nests of L. humile in the piles of damp leaves that had collected for the past month beneath some bushes. Watching the ants running away in freaked-out circles—probably spurred by that alarm pheromone Tsutsui mentioned—I couldn't help but feel sorry for them. After all, I'd wrecked their temporary homes. So I left a small piece of crushed fruit from our tree next to one of the nest entrances.

Call me an anthropomorphizer if you want. But even if we plant native species, cities are still going to be riddled with water pipes that keep L. humile from getting parched in summer. We might be able to keep their populations down, but we will probably never drive them out entirely. They've lived in California for 120 years, which is (again) equivalent to 120 ant generations. Will we always think of them as invaders? Can't we learn to live with them somehow? Sadly for those of us who empathize with these insect immigrants, living with the ants means killing some of them off. We don't yet know enough Argentine ant language to ask them politely to stop invading our homes and ecosystems. But we can manage their numbers in ways that do the least damage to other animals by using small amounts of poison and making our yards inhospitably dry.

Despite their elaborate communications systems, my Argentine ant housemates have not yet learned that plastic sugar boxes mean death. No, I have never been able to wipe them out, but for the time being I don't mind living with them as long as they stick to their territory in the backyard. I guess you could say I have reached a kind of detente with the Argentine ants, at least for now.

If you liked this story, read the sequel, a crazy science fictional tale of how the Ant Rights movement starts in the future. Only on Ars Technica UK!