https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-georgia-okeeffe-hawaii-paint-pineapples-dole

Georgia O’keeffe, Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast, No. 1, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Georgia O’keeffe, Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast, No. 1, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

It took Georgia O’Keeffe nine days to travel the 5,000 miles between New York’s Grand Central Station and the Hawaiian island of Oahu. Although she was heralded by local newspapers upon her arrival as the “famous painter of flowers,” the impetus for her trip was a different sort of plant life.

O’Keeffe was in Hawaii to paint a pineapple.

At least, that was what Dole (then known as the “Hawaiian Pineapple Company”) hoped she would do. It had approached O’Keeffe in 1938, proposing an all-expenses-paid trip to Hawaii—after which time the painter would deliver the company two canvases for use in a national advertising campaign. O’Keeffe was to determine the subject of these works herself, a degree of artistic freedom that likely encouraged her to accept Dole’s invitation despite an initial ambivalence.

Although TIME Magazine described O’Keeffe in 1940 as the “least commercial artist in the U.S.,” in reality the American painter had long dabbled in corporate commissions. One of her earliest jobs was as a commercial artist in Chicago, where she drew embroidery and lace designs for fashion advertisements. Later, after she’d achieved some measure of fame, she would contribute to the interior murals at New York’s Radio City Music Hall and paint four jimsonweeds in bloom for a Manhattan beauty salon.

Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe in Hawaii, 1939. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe in Hawaii, 1939. Via Wikimedia Commons. Georgia O'Keeffe, Pineapple Bud, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

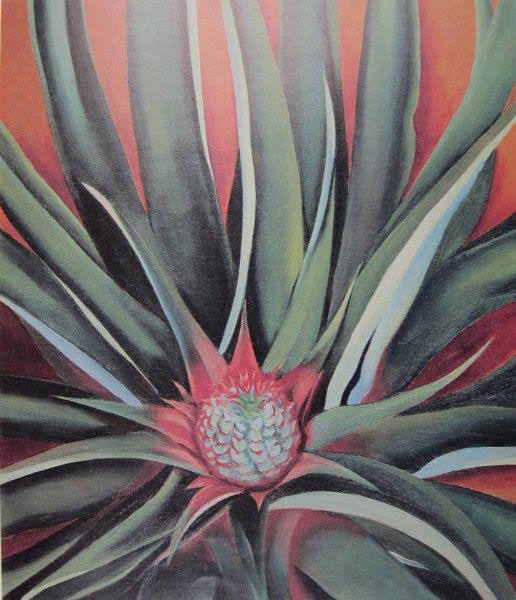

Georgia O'Keeffe, Pineapple Bud, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Dole’s offer had also come at precisely the right time. O’Keeffe was 51 years old, and she was living full-time in New Mexico while her beloved husband, photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, remained in New York. His ongoing affair with activist Dorothy Norman weighed heavily on O’Keeffe, who had suffered several nervous breakdowns throughout the 1930s. Equally troubling was an increasingly lackluster response to her work. Critics had begun to decry her emphasis on desert landscapes and motifs as nothing more than “a kind of mass production.”

So a change of scenery came with a particular kind of appeal. And at first, O’Keeffe’s visit to the Hawaiian islands proceeded smoothly. She arrived in Honolulu and was immediately enchanted by the pineapple fields, “all sharp and silvery stretching for miles off to the beautiful irregular mountains,” as she would say. “I was astonished—it was so beautiful.”

But when she asked for a residence near the plantation, Dole’s answer put a damper on O’Keeffe’s good spirits. The company denied her request, believing it would be improper for a woman to live among the laborers. (More recently, Dole has come under scrutiny for alleged labor rights violations on its banana farms.) Instead, it presented her with a peeled, sliced pineapple that the artist dismissed as “manhandled.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast No. 1, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast No. 1, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

So O’Keeffe set off across Hawaii, spending just over two months between the various islands. On Maui, in the isolated town of Hana, she met the Jennings family. Willis Jennings, who managed the local sugar plantation, enlisted his 12-year-old daughter Patricia to show the artist around.

Now in her eighties, Patricia recalls O’Keeffe being described as “difficult.” But during the 10 days the pair spent together, exploring an abandoned rubber plantation or the Seven Pools of ‘Ohe’o Gulch, the intimidating artist began to soften. Years later, O’Keeffe would write Patricia a letter recalling their time together: “Of course I will always remember you as a little girl—a very lovely little girl—in a sort of dream world.”

O’Keeffe also spent hours conversing with the personable Mr. Jennings, noting in a letter to Stieglitz: “By the time I leave the islands I am going to know so much more about sugar than I do about pineapples that is funny—”

In her accounts of the trip, she describes eating raw fish for the first time and donning straw sandals. She was mesmerized by Hawaii’s black cliff faces, but was unnerved by its active volcanoes with their steam issuing straight from the ground.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Crab Claw, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Crab Claw, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art. Georgia O’Keeffe, Waterfall—No. III— ‘Iao Valley, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Waterfall—No. III— ‘Iao Valley, 1939. Honolulu Museum of Art.

Finally, on April 14, 1939, it was time to leave. When O’Keeffe returned to the United States, she fell ill, and wasn’t able to deliver her paintings to Dole until the summer. When she finally did, the company received one rendition of the striking lobster’s claw heliconia and another of a papaya tree—but there was nary a pineapple to be seen.

Dole was less than pleased. In a last-ditch effort, the company shipped a pineapple plant from Hawaii to O’Keeffe’s doorstep in just 36 hours. Begrudgingly, she admitted it intrigued her. “It’s a beautiful plant,” she told TIME later. “It is made up of long green blades and the pineapples grow on top of it. I never knew that.” The resulting painting appeared in advertisements in both Vogue and the Saturday Evening Post.

O’Keeffe would visit Hawaii at least once more before she died. From its lush, verdant valleys to its stark black arches against a vivid blue sea—everything in Hawaii was diametrically opposed to the pastel desert landscapes that were O’Keeffe’s signature. But her Hawaiian paintings, as one critic noted at her 1940 show of the works, “testify to O’Keeffe’s ability to make herself at home anywhere.”

—Abigail Cain