Girl sitting at desk flipping through textbook pages at Putnam School. 1961. Gar Lunney. Canada. National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque. Library and Archives Canada, e010976007. CC by 2.0. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lac-bac/7797311412/

I would like to acknowledge and thank the many female instructors who got in touch with me over the past week, not only for their bravery in sharing their experiences with me, but for their strength in continuing in their dedication to the field of history and education. I am profoundly grateful and honoured.

“I think your feminist stances are slightly overcorrecting reality. I’m sure minorities had a harsher experience than women, ESPECIALLY today, a point you seem to overlook. You’re a really nice person though.”

That comment comes from my student evaluations from one of the first courses I ever taught, back when I was still a graduate student. At the time that I read that, I burst out laughing. I mean really, how else can you react to that kind of statement? But many courses and student evaluations later, I am starting to think that this is reflective of a larger problem in the world of academia, and history in particular, with respect to female sessional instructors and course evaluations.

Over the course of the past year or so, there have been a number of studies that have emerged detailing the gender bias against female instructors in student evaluations. According to one study, male professors routinely ranked higher than female professors in many areas.

[2] For instance, male professors received scores in the area of promptness (how quickly an assignment was returned) that were 16% higher than those of female instructors, even though the assignments were returned at the exact same time. Another research project, which examined word usage in reviews of male and female professors on “Rate My Professor” found that male faculty members are more likely to be described as “funny,” “brilliant,” “genius,” and “arrogant,” while female faculty members are more likely to be described as “approachable,” “helpful,” “nice,” and “bossy.”

[3]

While many of these studies discuss the negative impact that this bias has on tenure and promotion few consider how devastating they can be to sessional instructors, particularly given the overrepresentation of women at this academic rank.

Although data on sessional instructors in Canada, both contract and regularized, remains scarce, what we do know based on a

2016 report on sessional faculty at publicly-funded universities in Ontario is that 60.2% of sessional instructors identity as female. Most of these individuals have Ph.Ds. and will spend roughly 4 to 5 years working as a sessional instructors with the hope of securing full-time positions within academia. During these 4 to 5 years, 53.2% of these individuals will secure contracts that are less than 6 months in duration while the next largest group, at 18.2% will not have any current contract at all.

? And declining enrolment in history courses across the country means that jobs of any type are becoming more and more scarce.

The effectiveness of sessional instructors is often evaluated based primarily on student evaluations, particularly when it comes to questions of hiring, contract renewal, regularization, and promotion to tenure-track positions. (This is in spite of

solid evidence that student evaluations are not good measures of teaching effectiveness.) Consequently, female sessionals often face a serious disadvantage compared to their male colleagues.

Here is a quick sampling of some of the more problematic comments I’ve received over the years:

- “The focus on social history was good but I did not learn events leading to confederation. I didn’t come out of this course with any more information, except gender and race struggles, than I came in with.”

- “Although Andrea stated on the first day she would teach a peoples[sic] perspective it was not illustrated how much was going to be focused on first nations and women’s history.”

- “A bit biased in her views: very feminist and consequently an alternate view isn’t respected.”

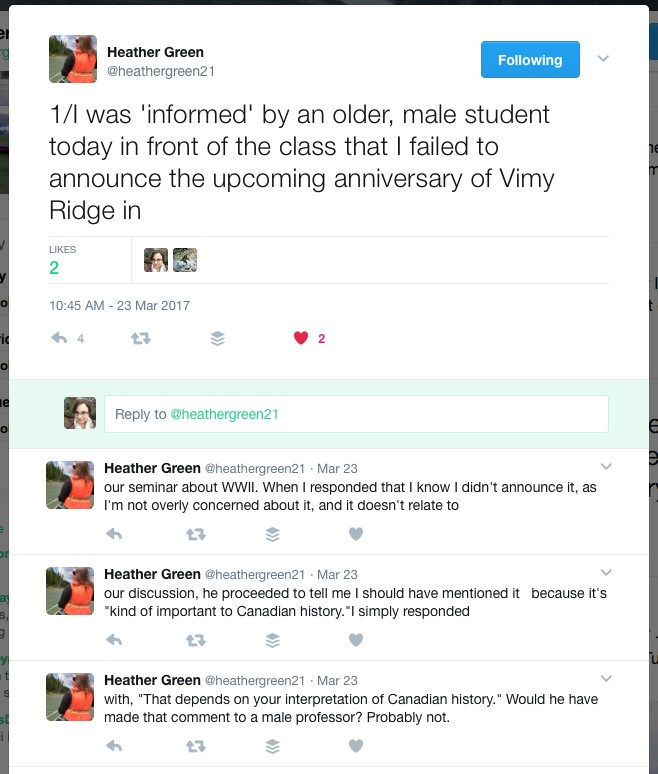

While these remarks only represent a small percentage of the student comments that I’ve received on evaluations, they are extremely troubling. They also appear to be fairly representative of the types of comments that female instructors, particularly those who appear to be younger, receive on a regular basis. While writing this piece, I put out a call on social media for Canadian female instructors who teach history to get in touch with me if they were willing to share some of these comments on an anonymous basis. Eight women came forward and shared their stories. These comments and stories generally fell into five categories: bias, inexperience, unprofessionalism, behavior/appearance, and sexualization.

One of the most common critiques is that of “bias.” You can see several examples of these types of comments that I’ve received above. Many female instructors are heavily criticized for including women and gender history in their courses, and this is often described as them imposing a personal bias on history. They are often accused of “only having one point of view” and “shutting down opposing views.”

For instance, one instructor had a student that complained, “it was obvious that she didn’t quite enjoy the boys telling her that men are biologically superior. She rapidly dismissed their explanations as outdated and sexist without giving them the reason (although she did later on in the course elaborate). But it was clear that those students had lost interest since their ideas were being rejected.”

Related to this problem are comments about female professors being “inexperienced,” “new,” or “too young.” Female instructors often have to face criticism from students who don’t feel that they are qualified to be professors. This is particularly a problem for female professors who appear to be younger than they really are or who happen to be short. Several of the instructors shared comments from students about them being “newer,” or just “getting started in teaching.” In one case, an instructor relayed that, “I also recently had an issue with a mature male student who made comments about me being “early in my career” and that he may be able to “help me” through his own line of work. He also expressed unsubstantiated doubts about my qualifications for teaching the subject matter after admitting to doing an online search of my background.”

Another common complaint is that female instructors behave “unprofessionally.” The reasons for this can vary significantly, but often relate to references to one’s personal life. For instance, one instructor I spoke with had been forced to cancel a class because her child was sick. She joked about it in the following class. Then, on her student evaluations, she noted the following comment: “I found it very unprofessional that the Instructor referenced her child as an excuse for not being available or for missing class. This is not the concern of the student or any reputable faculty. Those issues should remain private and availability should be clearly indicated without reference to the Instructors personal life.”

Female instructors are criticized on everything from their behaviour to their appearance. Many are told that they should “smile more” or be “more approachable and friendly.” One student wrote, “she sounds like a dictionary with all the words she uses.” In some cases, students comment on their clothing choices in student evaluations, with comments like, “I like how your jewellery[sic] matches your clothing” and “I would love to know where you shop. You have some great dresses.”

More pernicious are the sexualized comments that female instructors received. These ranged from comments that “she’s hot” and “the prof is not hard on the eyes” to “I would really like to get you into a room alone and have some fun.” Finally, one instructor was told “I like how your nipples show through your bra. Thanks.” As the instructor herself noted, “this one led me to never wear those bras again. I now wear lightly padded bras exclusively. I was horrified when I got this one. Horrified. And not because my nipples were showing. Who the eff cares? But because someone was looking at me that way and sexualizing me while I was teaching a class in political history.”

Instructors have handled such comments in different ways, but nearly all of the instructors that I spoke with have stopped reading comments on student evaluations entirely. This is particularly the case in more recent years, as student comments have become increasingly aggressive and at times violent. Not only are these comments not helpful in any regard, but also they are profoundly unfair.

The end result to these kinds of comments is a situation that puts female sessional instructors in an un-winnable position. Their job performance is judged on teaching evaluations that are significantly biased against them. And yet teaching evaluations are used to make hiring decisions, where female instructors are ranked alongside with their male peers, on the assumption of an even playing field. And when there are no second chances and bad teaching evaluations can spell the end of your entire teaching career, female instructors get the short end of the stick.

Each of these responses recommended that student evaluations should no longer be used to evaluate faculty members due to the significant gender, race, and other biases. They all specifically refuted the idea that careful design can be taken to counter the gender and racial biases in student evaluations. Instead, these reports advised that written comments in student evaluations should only be for the instructor’s use, and that alternative assessment tools be used instead, such as teaching practice inventory or correlating teaching with in one course with student grades in later courses. It remains to be seen what the final report will say.

While I can’t provide recommendations about what kind of system should replace student evaluations, what I can say is that based on the feedback that I’ve received and conversations I’ve had with other female instructors, gender bias in the classroom, and academia, is a serious problem that needs to be addressed openly, with honesty and compassion. Not only do these biases end careers, but they also deprive students of superb instructors.

This post is the first in a series of posts examining being female in academia and the realities of being a sessional instructor in today’s job market. If you have any stories you would like to share, please get in touch with the author at andrea [dot] eidinger [at] gmail [dot] com.

Andrea Eidinger is a historian of gender and ethnicity in postwar Canada. She holds a doctorate from the University of Victoria, and has spent the last six years teaching as a sessional instructor in British Columbia. She is the creator and writer behind the

Unwritten Histories blog, which is dedicated to revealing hidden histories and the unwritten rules of the historical profession.

[1] Special thanks to Joanna Pearce for her comments on the piece!

[2] Lillian MacNeil, Adam Driscoll, Andrea H. Hunt, “What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching,” Innovative Higher Education 40 (2015): 291-303. See also

Anne Boring, Kelle Ottoboni, and Philip B. Stark, “Student Evaluations of Teaching (Mostly) Do Not Measure Teaching Effectiveness,” ScienceOpen Research (2016): 1-11;

Patti Miles and Deanna House, “The Tail Wagging the Dog: An Overdue Examination of Student Teaching Evaluations,” International Journal of Higher Education 4, no. 2 (2015): 116-126; and

Natascha Wagner, Matthias Rieger, Katherine Voorvelt, “Gender, Ethnicity and Teaching Evaluations: Evidence from Mixed Teaching Teams,” Economics of Education Review 54 (October 2016): 79-94.

[4] Thank you Christo Aivalis for the suggestion of this example. The comments section of this article (and many similar articles) highlights the prevalence of the ‘just ignore’ attitude.

[5] To see the background research for the study as well as some of the other responses and commentaries, including those from students, click

here. Interestingly, of the responses posted that website, only the Federation of Students was fully supportive of the draft report’s recommendations.