Following

a long journey from Ireland to New York on the S.S. Essex, Miss Bridget

Cork arrived in New York City on February 14, 1894, and was delivered

to Mayor Thomas F. Gilroy at City Hall.

The Duke arrived in Chicago by way of New York City, where he spent several days touring the city with Mayor Thomas Francis Gilroy and other members of the city’s Columbus Reception Committee of One Hundred.

So what does Christopher Columbus, Mayor Thomas Gilroy, and a Spanish Duke have to do with an Irish cat from County Cork? Well, it is because of the Duke’s visit to America that this quaint story about an Irish cat named Miss Bridget Cork can be told. In fact, one could almost say this cat story is tied to the discovery of America. Okay, maybe I’m stretching it a bit, but I couldn’t resist the opportunity.

New York City, Washington, D.C., St.

Louis, and Chicago had all vied to host the World’s Columbian

Exposition. In fact, it was during this spirited competition that

Charles A. Dana, editor of the New York Sun,

dubbed Chicago “that windy city.” On April 25, 1890, President Benjamin

Harrison signed the act that designated Chicago as the site of the

exposition. The event was supposed to take place in 1892, but it took

longer than expected to prepare and produce the exposition.

Our story begins on April 23, 1892, the day President Grover

Cleveland sent the Duke of Veragua an invitation to attend the opening

ceremonies at the World’s Columbian Exposition as a guest of the

government and the people of the United States. The Duke arrived in New

York a year later on April 15, 1893, aboard the American Line steamship

appropriately named S.S. New York, accompanied by his wife,

Dona Isabel de Aquilera, the Duchess of Veragua; his son, Don Cristobal

Colon de Aguilara; his daughter, Dona Maria; his brother, the Marquis of

Barbolis; and the Marquis’ son, Pedro Columbus de la Corda.

Born

in Madrid in 1837, Don Cristóbal Colón de Toldeo de la Cerda y Gante,

Duke of Veragua, Marquis of Jamaica, and Admiral and Adelantado, Mayor

of the Indies, was the thirteenth in direct descent from Christopher

Columbus.

During his time in the city, the Duke and his family were guests of numerous grand receptions at City Hall, the Waldorf, and other locations throughout the city. The Duke of Veragua also visited Mayor Thomas F. Gilroy at his home in Harlem at 7 West 121st Street, took a tour through Central Park, and visited Grant’s Tomb.

Following a three-month stay in America, the Duke, his family, and their 92 shipping trunks departed New York on board the French liner La Bretagne. Despite being entertained by the city in a most elaborate fashion, the Duke reportedly left without giving the mayor or any other political dignitaries a thank-you letter or gift.

Commander Dickins apparently had better manners…

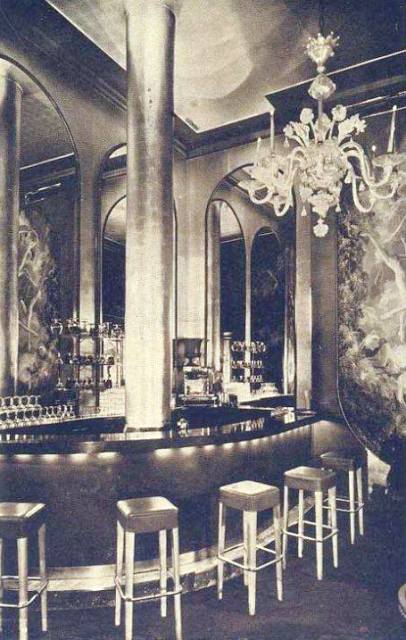

The Duke of Veragua and his family

were the first guests to stay in the Waldorf’s state apartments, a suite

of nine rooms for visiting foreign dignitaries located on the second

floor, overlooking Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street. Pictured here is the

Henry IV drawing room. Built in 1893 and connected to the Astor Hotel in

1897, the Waldorf Hotel – later the Waldorf–Astoria – was razed in 1929

to make way for construction of the Empire State Building. Princeton University Library

A Cat Arrives at City HallOn February 14, 1894, a pine box with slats on top arrived at New York City Hall. Acting Secretary McDonough was not sure what to make of the box, and was even worried that it might contain a dangerous device.

“What is it?” asked Mayor Gilroy. “A cat!” McDonough replied, after hearing the cat meow. “By George, there’s a real Gaelic tone to her voice,” said one joker in the office. “Yes, and she has County Galway whiskers,” said another.

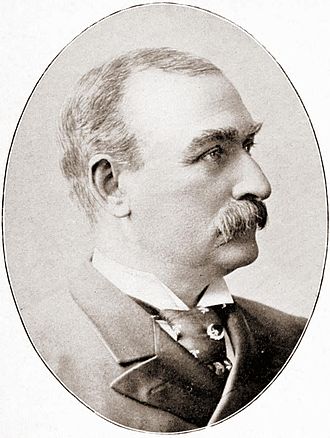

Born on June 3, 1840, in Sligo, Ireland, Thomas Francis Gilory was

a key member of the Tammany Hall organization, beginning as a messenger

for “Boss” William Tweed, and serving as confidential secretary for

Henry W. Genet, Tweed’s Tammany Hall successor. He was New York City’s

89th mayor, serving just one term from 1893-94.

My Dear Mayor Gilroy:

Last August I sailed from the United States, with the United States ship Monongahela under my command, for Queenstown, Ireland. Upon our arrival and during our stay there we received the most hearty welcome and gracious hospitality from all the Irish people, and particularly so from the gallant Mayor of Cork, the Hon. Augustine M. Roche.

Remembering your kindness to me in New York when I had the honor to represent the President of the United States in charge of the courtesies to the Duke of Veragua while he was the guest of the Nation, I wanted to bring back to you some token from that beautiful country, and the Mayor of Cork kindly gave me—not a tiger—but a gentle cat with a heart whose warmth is only exceeded by those of her countrymen.

Hence, I send to you today, by express, Miss Bridget Cork, accompanied by appropriate verses, composed by Mrs. Franklin Weld of Boston, with a chorus set to music. The clever lines I hope will please you, and that you will accept Miss Bridget with my profound gratitude, and with the best wishes for her welfare as well as your own, believe me to me, very sincerely yours, F.W. Dickins, Commander U.S.N.

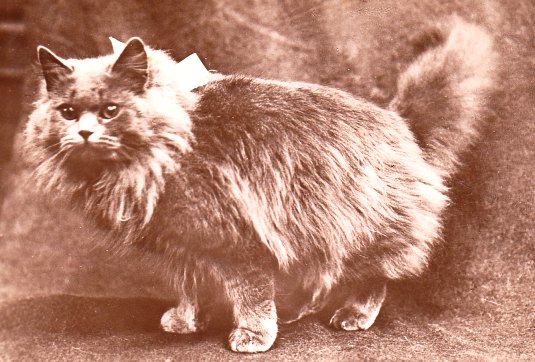

Described in The New York Times as a handsome, good-natured purring cat, with a soft coat of dark gray and stripes of a darker hue, Bridget Cork had traveled from Queenstown to America with Commander Dickins on the SS Essex, which had arrived at the Norfolk Navy Yard on February 11. She then traveled by train to New York City in the pine box.

Commander Francis William Dickins, 1898

God speed to you, Captain Dickens, On your voyage across the sea!

Bear to Gilroy, Mayor of New York, The warmest of greetings from me.

From Ireland here to the Irish there, Good luck and comfort and care;

May they ne’er forget their country, In their homes across the sea.

The home land! The heart land! Through their homes are there, their hearts we share. Hurrah for the ould countrie! New York, ahoy! Here’s to Mayor Gilroy, to Roche and the Irish cat!

Writing is too cold and measured, And for words we are too far apart;

So warm hearts here send in greeting to you, A warm little Irish heart–

A symbol of comfort and luck, A real little Irish cat.

With Irish for pluck and a cat for luck, Can I send better than that?

The luck land! The pluck land! The Irish for pluck, the cat for luck. Hurrah for the Irish cat! New York, ahoy! Here’s to Mayor Gilroy, to Roche, and the Irish cat!

Although she wasn’t any match for Thomas Nast’s Tammany Tiger, Mayor Gilroy was quite pleased with the cat — and Bridget was quite pleased to be out of the box — but he knew there was no way she could stay at City Hall. After all, City Hall already had Tom, its brazen feline mascot, and Tom would never have accepted another cat in his territory. So Mayor Gilroy sent Bridget to his home on West 121st Street, where I’m sure she received plenty of attention from the mayor’s ten children.

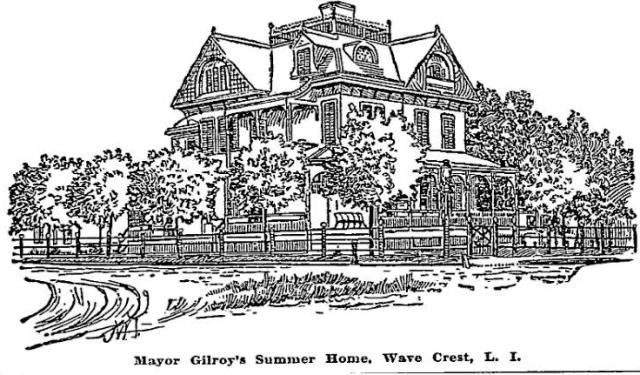

Perhaps Bridget Cork was lucky enough

to spend her summers with the Gilory family at their home on Ocean

Avenue (near present-day Ocean Crest Boulevard and Bay 32nd Street). The

large white house with green trim fronted away from the shore, and from

the back yard one could see the ocean, and in the distance, Sandy Hook,

New Jersey. Thomas Gilroy died in this home on December 1, 1911. He was

buried alongside his wife, Mary, at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

1921 & 1936: Billy and Rusty, the Famous Felines of the Algonquin Hotel

Posted: March 7, 2015 in Cat Mascots, Cat Stories, Feline MascotsTags: Algonquin Cat, Algonquin Hotel, Ben Bodne, Frank Case, Matilda III, New York History

5

Some

sources claim that actor John Barrymore, a frequent guest of the hotel,

changed Rusty’s name to Hamlet. Barrymore was a big fan of cats, and he

did play Hamlet on Broadway, but every newspaper article from that era

calls the cat Rusty. No news articles from the 1930s or 40s mention a

cat at the Algonquin named Hamlet.

Like most stray cats, he was fighting for survival on the streets, and a hotel lobby was as good a place as any to search (or beg) for food and shelter.

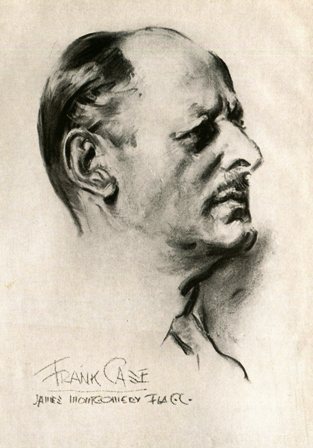

Frank

Case, the legendary owner of the Algonquin, welcomed this feline hotel

guest, even though he was just a ragamuffin street cat. Somehow he knew

there was something special about this orange cat with the perfect tabby

markings. Plus, the hotel needed a new cat to replace Billy, who had

arrived at the Algonquin around 1921 and had lived there happily for 15

years.

Frank

Case, the legendary owner of the Algonquin, welcomed this feline hotel

guest, even though he was just a ragamuffin street cat. Somehow he knew

there was something special about this orange cat with the perfect tabby

markings. Plus, the hotel needed a new cat to replace Billy, who had

arrived at the Algonquin around 1921 and had lived there happily for 15

years.Frank Case named the cat Rusty, and well, as they say, the rest is history.

The

Algonquin Hotel was built in 1902 following the demolition of two brick

stables and two frame buildings on land once occupied by the farm of

John N. Grenzebach. When it opened on November 22, it was a residential

hotel with apartments that could be rented for an annual rate of $420

for a simple one-bedroom and bath to $2,520 for a luxurious suite of

three bedrooms, private dining room, parlor, library, three bathrooms

and private hallway. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Matilda III is the current cat of the house. She took over when Matilda II retired at the age of 15 and moved to a staff member’s home in December 2010. A beautiful ragdoll cat (although she sometimes reminds me of Grumpy Cat), Matilda III was rescued after being abandoned in a box outside the North Shore Animal League in Port Washington, New York.

The Legend of Rusty

Rusty, the Algonquin’s “snooty cat…ignores more celebrities than the Social Register…it’s whispered around by those who claim to know that he really runs the place.”– Dorothy Kilgallen, the “Voice of Broadway”

Rusty

received numerous letters from his fans, and every year he was

recognized for donating to the March of Dimes, but that’s nothing

compared to the attention Matilda gets. As a cat of the digital age,

Matilda is probably the most popular Algonquin Cat yet. She’s all over

the Internet, and even has her own Twitter account, Facebook page, and email!

Over the years, Rusty grew into a very distinguished cat, weighing 18 pounds at his prime. He was a favorite among the actors and artists and writers that frequented the hotel, and he especially loved new guests.

Rusty would greet and nudge each new guest warmly and incorrigibly – he’d often have to be pushed off the register to they could sign it (what is it with cats and newspapers and books?).

In

early years, the hotel allowed its temporary residents to have dogs, so

Rusty had quite a few run-ins with canines. One time a French poodle

that was staying at the hotel gave Rusty quite a tussle, and the poor

cat hid under a bed for several days. He got sympathy cards from many

famous people, including Sinclair Lewis, author of Main Street, Babbitt,

and other works.

Once presentable, Rusty would take the elevator downstairs to assist the Algonquin staff. For Rusty’s convenience, a little swinging door between the lobby and the kitchen was installed so he could help with the kitchen staff.

However, he spent much of the day in the Blue Bar with Louie the bar waiter, where he had a special stool reserved just for him. He’d show up for duty around 11 a.m. when guests began arriving, and keep guard until around 3 p.m. when the lunch crowd thinned out.

Rusty spent much of the day in the Blue Bar with his pal Louie the bar waiter.

Then promptly at 4 p.m. he’d jump off his stool and get back on the elevator in the lobby with his guardian, Mrs. Germaine Legrand, the Case family’s housekeeper (he always took the passenger elevator, never the service elevator!).

Back in the Case suite, Rusty would get a snifter of milk in a champagne glass and then take an afternoon cat nap. At 7:30 p.m., he’d appear at the bar again for his next tour of duty, and then head back upstairs for the night at 10 p.m.

In

early years, the Algonquin offered an in-house physician, barber,

hairdresser and manicurist who would make calls to rooms. It also had a

barbershop for guests (I don’t know if Rusty had his own chair here, but

I doubt he ever asked for a haircut!) Museum of the City of New York

Collections

Summers were extra special for Rusty, because he got to take a break from the big city and spend weekends at the Case family’s summer home, Shore Acre Farm, on Actors Colony Road in the village of North Haven (Southampton), Long Island.

Frank Case purchased the waterfront summer home in June 1919 from Mrs. Lilian Backus, the widow of Eben Y. Backus, who was the stage manager for the Empire Theatre on 42nd Street. The home was located in a cottage colony of actors (hence the street name) and many famous thespians who also lived or vacationed at the colony, including Douglass Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, would often visit the family and their cat Rusty.

The Case summer home – formerly the Backus cottage (middle right) — was located just north of the old Charles M. Goodsell cottage and farm, where Julian Hawthorne, the son of author Nathanial Hawthorne, had spent a summer in 1820. The 92-acre estate on the Shelter Island Sound was purchased by the Sag Harbor Estates Company in 1910, which built a cottage park that they called Hawthorne Manor. The colony was purchased by the Conservative Land Associates in 1925, with plans to subdivide the land further for “high-class small homes.”—NYT, November 18, 1925

On February 21, 1946, five years after Rusty won a long battle with pneumonia, Bertha Case succumbed to a year-long illness and died in the Case’s hotel suite. Four months later, on June 7, Frank Case died in the hotel.

Following his death, Frank’s body was laid in state in the suite. John Martin, manager of the hotel, held Rusty in his arms and let him take a last look at his master. Martin told the press that as he held him, a shudder appeared to go through the cat’s body. He also uttered a strange cry.

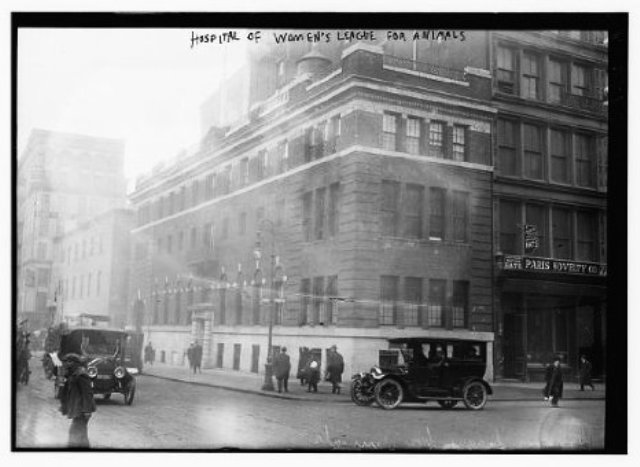

In

April 1941, Rusty came down with pneumonia and had to spend some time

in an oxygen tent at the Ellin Prince Speyer Animal Hospital for Animals

at 350 Lafayette Street. Formerly known as the Hospital of Women’s

League for Animals, the facility opened in 1914.

Less than two weeks after Frank’s death, John found Rusty in the suite, curled beside the bed of his old master. The jaundice and feline leukemia were no doubt the cause of his death, but those who knew him, like Mrs. Legrand, said he simply died of a broken heart.

“Rusty was sick from missing the two people he loved best,” Mrs. Legrand told The New York Sun. “Always he was looking at the door as if he wondered why they didn’t come.”

According to the East Hampton Star (August 15, 1946), Rusty was buried in the place he spent many a summer day with the Case family and their famous theater friends — in the Case garden at their summer home in Southampton.

In

1924 Ben B. Bodne and his bride Mary (with Harpo Marx) honeymooned at

the Algonquin. At the time, he promised Mary he would one day buy the

hotel for her. Soon after Frank Case died in 1946, Ben Bodne retired

from the oil business and acquired ownership and operation of the hotel.

I guess this 21st-century directive means there is no longer a special stool at the bar reserved just for the hotel’s feline and no longer a kitty door to the kitchen. Although he didn’t have a Twitter account, a Facebook page, or an email address, Rusty had it pretty good in those simpler, rule-free days.

Rusty

was buried in the Case family garden at their summer home on Sag

Harbor, somewhere in the vicinity of today’s Cedar Avenue. Considering

the fact that all this land is now worth countless millions of dollars –

even Richard Gere had a house nearby until recently – Rusty’s final

resting place is pretty darn nice for a former alley cat.

1934: Arson and Homicide, the New York Cats on the Job at Police Headquarters

Posted: September 22, 2014 in Cat Mascots, Cat Stories, Feline MascotsTags: 240 Centre Street, 300 Mulberry Street, Cat Stories, Centre Market, New York History, New York Police Headquaters, NYPD, police cat

This is not Homicide, but he looks the part.

Homicide sauntered into the New York City Police headquarters building at 240 Centre Street sometime in January 1934. The large black cat with translucent green eyes and prominent whiskers couldn’t have chosen a more magnificent place to work and live.

The

monumental Beaux-Arts style building, which opened in 1909, featured a

grandiose entrance hall and such amenities as a basement shooting range

and printing center, carpeted offices for the commissioner and officers

on the second floor, third-floor library, fourth-floor gymnasium with

drill room and running track under the roof dome, fifth-floor radio

broadcasting station and telephone exchange (formerly a telegraph

bureau), and a rooftop observation deck. Museum of the City of New York

For the one thousand or so men attached to police headquarters, Arson’s departure was not a mournful event. You see, Arson was more like a Keystone Cat who was simply not cut out for the job. Although Arson loved his beat, he never made a collar. What he did make was noise – so much so, that even when he walked on carpeted floors the mice could hear him in time to scamper away to safety.

“And that’s why we called him Arson,” Lieutenant James R. Smith told reporters from The New York Times. “He was all burned up because he never caught a mouse.”

Homicide, on the other hand, was very light on his feet. He was also a very conscientious police cat, always starting his beat every night at 6 and covering every mouse hole from the basement to the roof. He may not have attended police academy, but he did have great respect for the Police Rules and Regulations book – he often took cat naps on top of the great book.

Down in the cellar Homicide would search all the prisoner cells, and from there he’d move up to the first floor, where he would search the safe, squad rooms, Bureau of Criminal Identification, and Criminal Alien Bureau. And, unlike Arson, who simply passed up a room if he couldn’t get in, Homicide would stand in front of every locked door and give his best police whistle meow until one of the sergeants came to assist him.

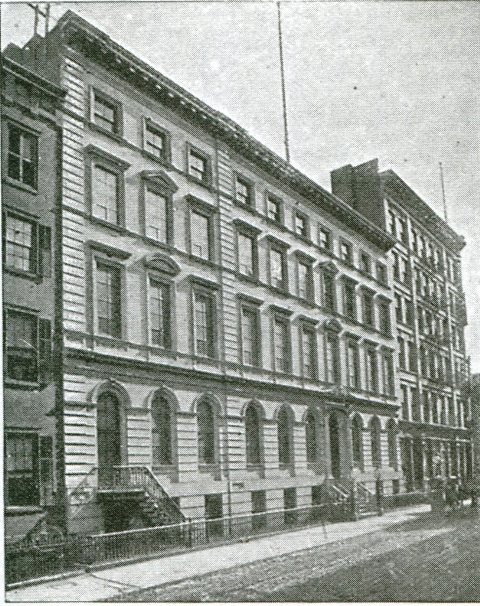

The

5-story, 90-foot-wide police headquarters building at 300 Mulberry

Street was constructed of white marble and pressed brick with white

marble trimmings. The building was erected in 1862 and first occupied in

1863.

On one particularly warm night in July 1934, Homicide ambled down to the cell blocks, where a few prisoners were drowsing in the heat. He quietly perched over a particularly dangerous mouse hole, narrowed his eyes, and patiently waited for the perp to appear. When it did, he leaped at the good-size mouse and captured the convict in his jaws.

As the prisoner struggled to escape, Homicide ran up the stairs to the first floor, sprinted down the corridor, and jumped up onto the main desk, where Lieutenant Smith was sitting. He dropped the exhausted prisoner on the desk blotter, gave Smith a salute with a nod of his head, and ran back down to the basement to continue his beat.

“I’ve seen them come and go, in my time, but never before a cat that brings ‘em back alive and books ‘em,” Smith told the news reporters. “I’m recommending a citation for an extra ration of liver. Homicide’s a first-grade cat, from now on.”

Centre Market and the New York City Police Headquarters

Arson and Homicide were no doubt two of the most fortunate police cats in the history of the feline force. Not only did they get to live in police headquarters, but their beat was immense, with enough rooms and hiding places to satisfy any cat’s curiosity. Consider that today movie stars like Leonardo DeCaprio and Cindy Crawford are paying millions of dollars to live in one of the luxury condos in the renovated building – now called the Police Building Apartments.

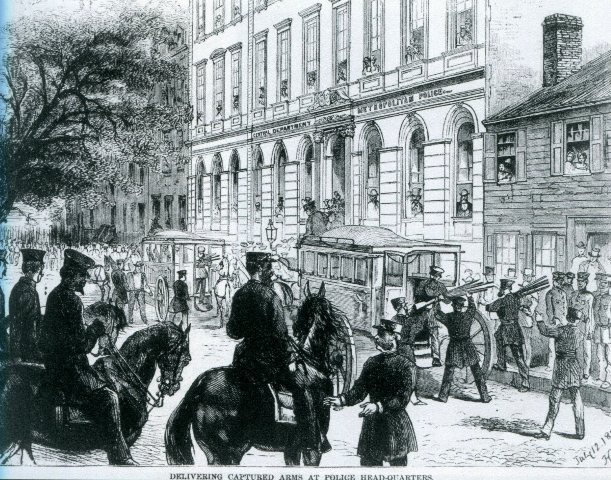

The police headquarters on Mulberry Street had to be protected with a strong militia during the Orange Riots of 1871.

In 1857, headquarters were established at 88 White Street, and six months later, at 413 Broome Street. In 1863, the department took possession of its new headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street.

Police

Commissioner Partridge wanted to build a new police headquarters on the

site of the Central Market, a large meat and produce market bounded by

Broadway, 7th Avenue, West 47th and West 48th Street.

In September 1902, Police Commissioner John N. Partridge suggested the site of the Central Market on 7th Avenue between West 47th and 48th Streets for a new police headquarters building. But one month later, Chief Engineer Eugene E. McLean of the Department of Finance submitted a report on the decrepit condition of the public markets in Manhattan. In this report, he recommended demolishing the Centre, Clinton, Union, Tompkins, and Catharine markets. McLean also suggested constructing the new police headquarters on the site of the old Centre Market, which was located on a large triangular lot on Centre Street between Broome and Grand streets.

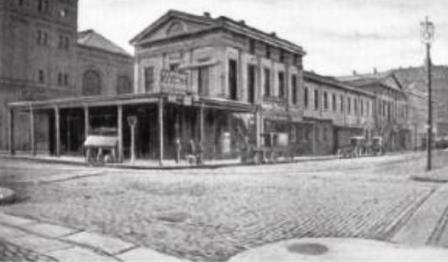

The

Centre Market derived its fame from being the only centrally located

market in the city. This original Greek-Revival building was expanded in

1822, and again in 1826 and 1831.

In 1812, a proposition was made to establish a public market on a site located between Orange (Central Market Place) and Rynders Street (Centre Street), facing Grand Street. Located on what was once the Nicholas Bayard farm, this site was formerly known as Bayard’s Mount, as it was the highest and steepest elevation on the south end of Manhattan island. During the early stages of the American Revolution, the elevated land was fortified and called Bunker Hill.

The proposition was tabled due to the War of 1812, but in July 1817 the city purchased the lot from Morris Martin for $5,000. A market house, measuring 80 by 25 feet, was also planned at an estimated cost of $1,000. The market opened in November 1817, and the 14 butchers holding stands at the Collect Market (located between Broadway, Cortlandt Alley, and Walker Street) transferred to the new Centre Market.

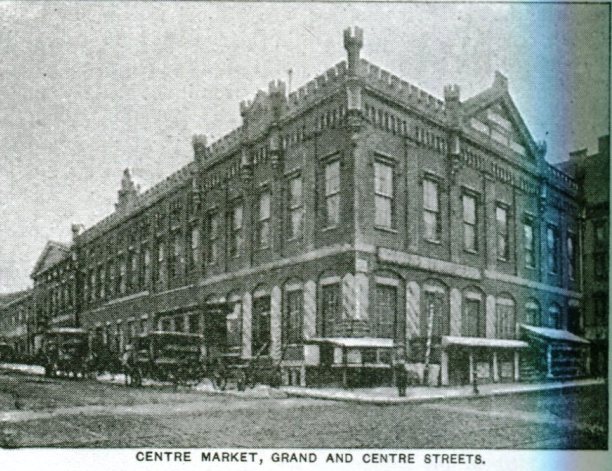

On

January 17, 1839, the $140,000 Centre Market opened with a grand ball

and supper given by the butchers in the large upper rooms. These room

would later become a drill hall for the military. Museum of the City of

New York Collections

Upstairs from the market stalls was a large drill room for the Seventh Regiment (until it relocated to the Central Park Arsenal in 1848), and later, for the Sixth, Eighth, and Seventy-First Regiments. Up until about 1857, several upper rooms were also occupied as a station house for the 14th Patrol District (later the 14th Police Precinct).

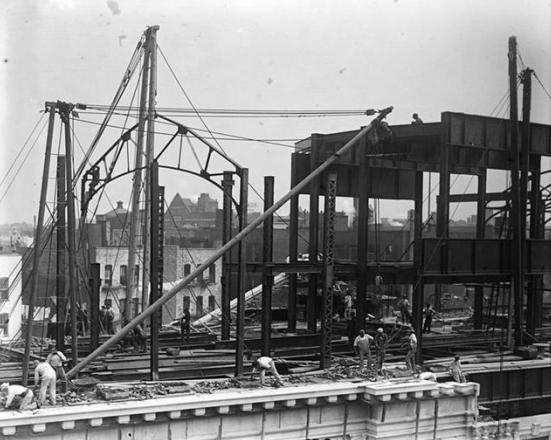

Paper box manufacturer and grand prankster Brian G. Hughes

was leasing part of the Centre Market when it was purchased by the city

for the police department. Here, his section of the market is being

demolished in preparation for the new construction. Museum of the City

of New York Collections

The

top floor of the police headquarters building at 240 Centre Street was

constructed in 1906. The opening of the new building was delayed by

construction of the Lexington Avenue subway, which runs directly under

it. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Theodore Roosevelt, a former police commissioner, reportedly laid the cornerstone for the new headquarters, and, six years later, in November 1909, the transition from Mulberry Street to Centre Street began.

Police Commissioner William F. Baker formally opened the new police headquarters building at midnight on November 29, 1909. His first act was to press a key that switched all the telegraph and telephone lines from the old building at 300 Mulberry Street into the telegraph bureau on the fifth floor of the new building.

The boxy One Police Plaza looks more like a dormitory building one would see on a college campus.

By 1929, New York City Police Commissioner Grover Aloysius Whalen was already complaining about the 20-year-old building, saying he wanted to replace it with a bigger place – perhaps a skyscraper, about 20 stories tall. It would be another 44 years before he got his wish, and the new headquarters were six stories short of his ideal.

In 1973, the New York City Police Department moved to One Police Plaza, a red-brick box on Park Row near City Hall and the Brooklyn Bridge. The glorious old headquarters building sat empty for years until finally, in 1983, the city accepted the proposal of developer Arthur Emil to turn it into luxury condominiums. Emil paid the city $4.2 million and spent another $20 million on renovating the building.

Today the building has 55 high-end condos, including one of the most unique residences in New York City: the 10-room apartment in the former gymnasium. Click here for a look at this spectacular unit, which hit the market a few years ago for $14.5 million. Or, take a look at a few other apartments for sale.

I think all that’s missing from these condos are a few good police cats, like Homicide and Arson.

The

grandiose entrance hall of the old police headquarters has been

preserved and restored, but most of the interior was gutted and redone.

Today, residents of 240 Centre Street — aka Police Building apartments

— have access to several luxury amenities, including a 24-hour doorman,

concierge, fitness center, and large, private garden. Pets, including

cats, are allowed.